A “demilitarized autonomous zone” has been proposed as a solution for a gradual lessening of Israeli administration of the territories of Judea, Samaria and the Gaza Strip. At some point in the ongoing Middle East peace talks, the exact legal meaning of the term “demilitarized autonomous zone” will have to be agreed upon by Israel, the surrounding Arab states, the Palestinians and, if necessary, outside peace keeping guarantors. (Ed. note: The recently elected prime minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin, has announced that negotiations on Palestinian autonomy in the territories will proceed rapidly.)

One problem facing Israeli negotiations will be a structure to prevent determined individuals from smuggling impermissible weapons into the “demilitarized zone.”

In this regard, the Israeli negotiating team must grapple with the reality that, no matter what settlement is reached, there will continue to exist well-funded, organized and violent Palestinian nationalistic and Islamic extremist elements which will attempt to smuggle weapons into the “demilitarized zone” which they will use to kill Israelis.

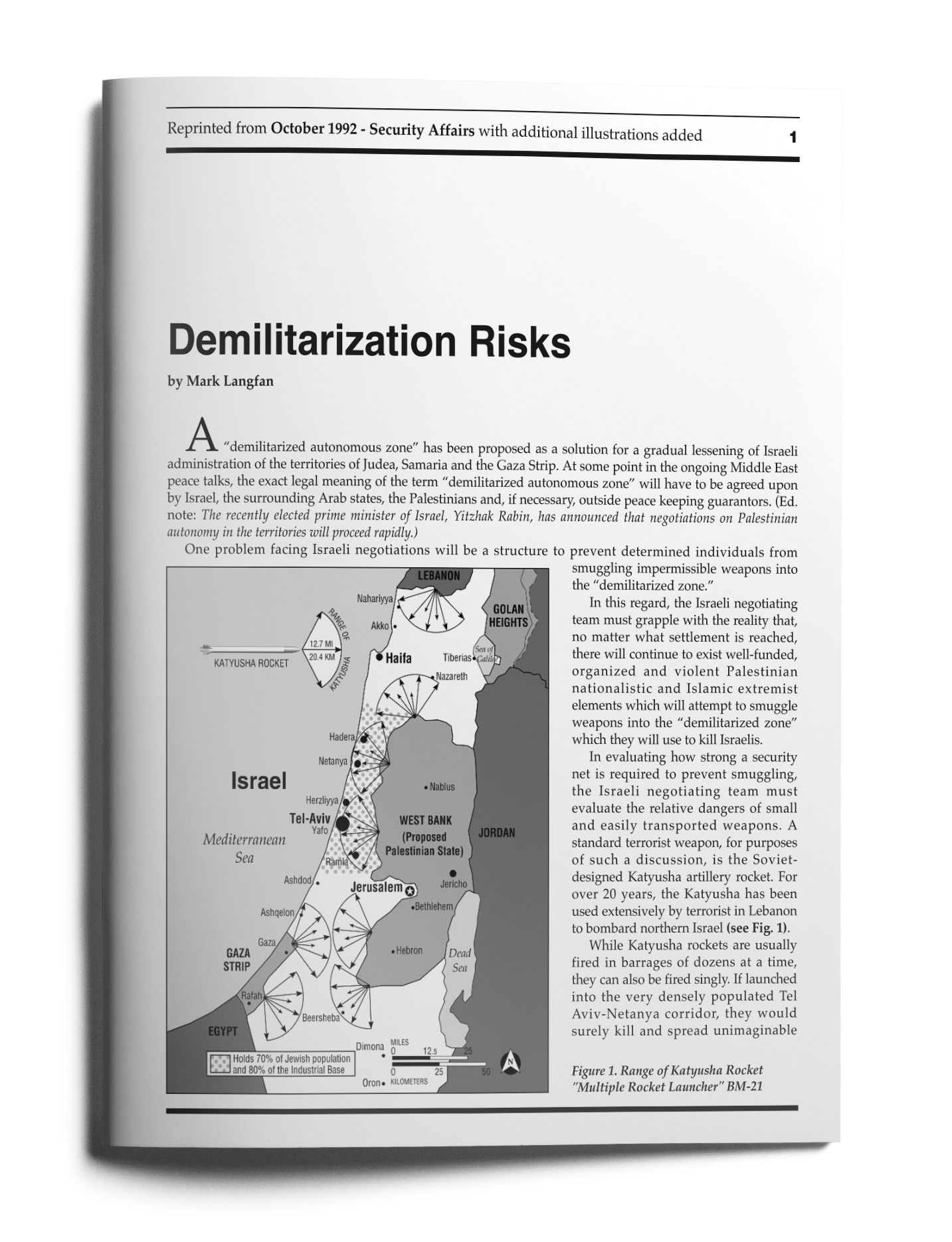

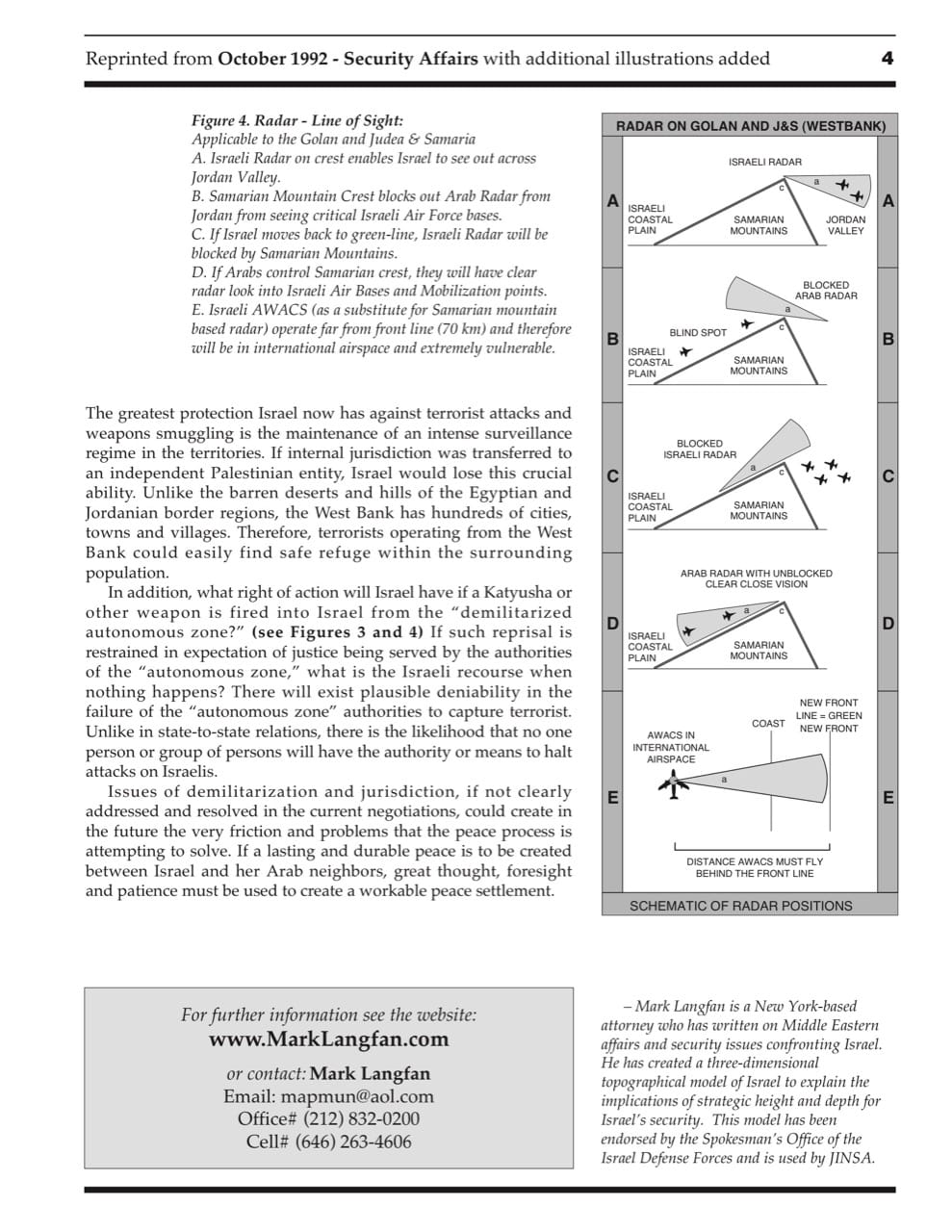

In evaluating how strong a security net is required to prevent smuggling, the Israeli negotiating team must evaluate the relative dangers of small and easily transported weapons. A standard terrorist weapon, for purposes of such a discussion, is the Soviet- designed Katyusha artillery rocket. For over 20 years, the Katyusha has been used extensively by terrorist in Lebanon to bombard northern Israel (see Fig. 1).

[/et_social_share_media]

[/et_social_share_media]

Figure 1. Range of Katyusha Rocket "Multiple Rocket Launcher" BM-21

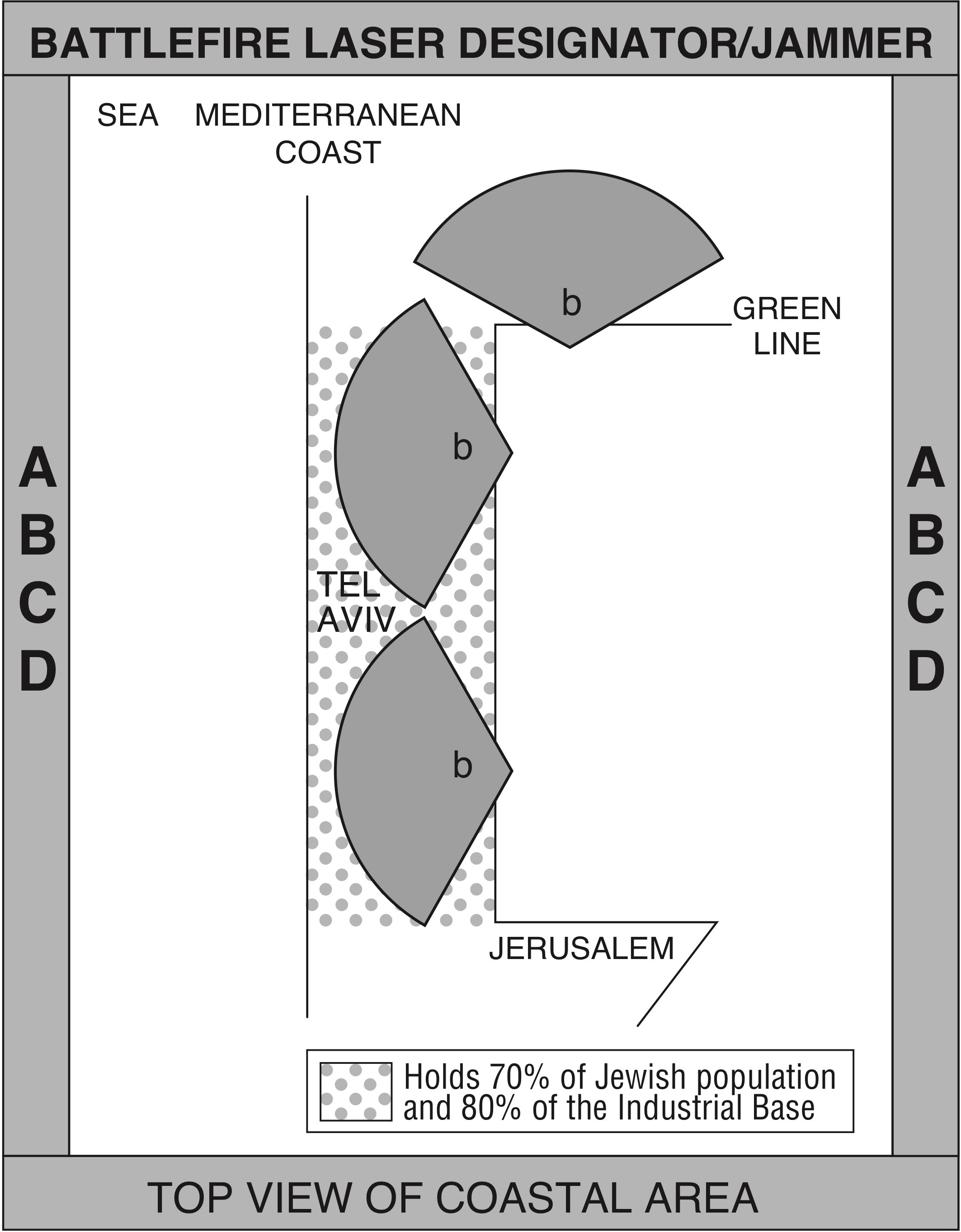

While Katyusha rockets are usually fired in barrages of dozens at a time, they can also be fired singly. If launched into the very densely populated Tel Aviv-Netanya corridor, they would surely kill and spread unimaginable terror (see Fig. 1 and 2). Israel’s coastal corridor contains 70 percent of Israel’s population and 80 percent of her industrial base.

[/et_social_share_media]

[/et_social_share_media]

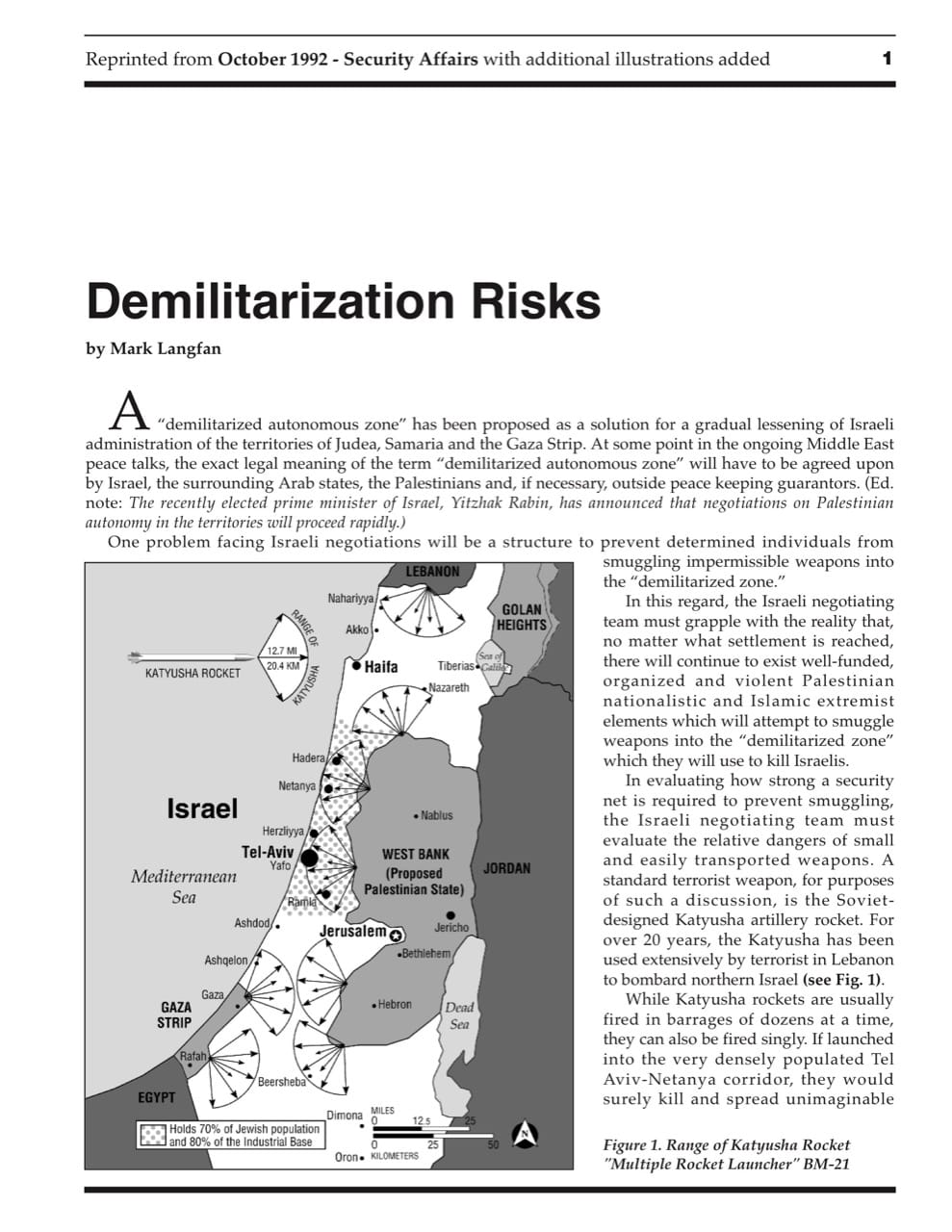

Figure 2. Schematic of "What if:"

- A. Katyusha is fired by a “terrorist” element?

- B. Illegal radar is turned on by “terrorists?”

- C. Illegal laser designator is turned on by a “terrorist” element?

- D. Illegal radar jammer is turned on by a “terrorist” element?

- E. The large coverage effects and the concerns raised by these hypothetical question can be clearly visualized using 2 or 3 plexiglass pieces on a standard 1:250,000 map.

[/et_social_share_media]

[/et_social_share_media]

The Katyusha (or BM-21) is a Soviet designed, solid propellant rocket with a range of approximately 13 miles or 20 kilometers. It carries a 43-pound warhead containing either high-explosive, antipersonnel shrapnel, or chemical agents and is normally carried in a 40-tube launcher mounted on a truck, but individual rockets have been fired at Israeli territory from South Lebanon with nothing more than a length of metal pipe and a car battery to ignite the propellant.

The Katyusha is cheap and easy to produce and very powerful. One salvo of 40 Katyushas is the equivalent of 1720 lbs. of high- explosive or approximately the weight of four of Iraq’s extended-range Scud missile warheads! And they’re powerful too. In February 1992, Hezbollah terrorists fired a Katyusha into Israel striking a bus station in the northern city of Kiryat Shmona. That single Katyusha warhead punched a 2.5 foot by five foot hole through six inches of reinforced concrete. A house or the roof of a civilian apartment would have been destroyed by a single Katyusha, and an entire block of apartments would be destroyed by a salvo. The rocket’s 13-mile range easily covers the distance from the West Bank to Israel’s populated coastal region.

The technological simplicity and ease of transportability of many weapon systems with sufficient range to cause havoc and death in Israel make smuggling of weapons into the West Bank a grave concern for Israeli negotiators.

A lengthy series of questions must be answered: who will be the border guards at authorized points of entry? Will they be Israelis, Palestinians, United Nations personnel or some combination? If someone is caught trying to smuggle in a weapon, who will have the jurisdiction and right to confiscate the weapon and take the smuggler into custody? What rights will the accused be afforded? Who will have the right to interrogate the smuggler, and what forms of interrogation will be permissible? What happens if the individual flees into the “demilitarized autonomous zone” outside the jurisdiction of the border guards Do the guards have the right to pursue the escaping smugglers.

Under what conditions and with what force can border guards attempt to arrest a fleeing weapons smuggler? What will be the rules of engagement between pursuing border guards and the internal jurisdiction authority of the “demilitarized autonomous zone?” A secure border requires not only border guards at a authorized points of entry but also a highly vigilant and effective mobile force to stop other methods of weapons smuggling, including those by the air or sea.

Internal security measures are another issue to be addressed. The greatest protection Israel now has against terrorist attacks and weapons smuggling is the maintenance of an intense surveillance regime in the territories. If internal jurisdiction was transferred to an independent Palestinian entity, Israel would lose this crucial ability. Unlike the barren deserts and hills of the Egyptian and Jordanian border regions, the West Bank has hundreds of cities, towns and villages. Therefore, terrorists operating from the West Bank could easily find safe refuge within the surrounding population.

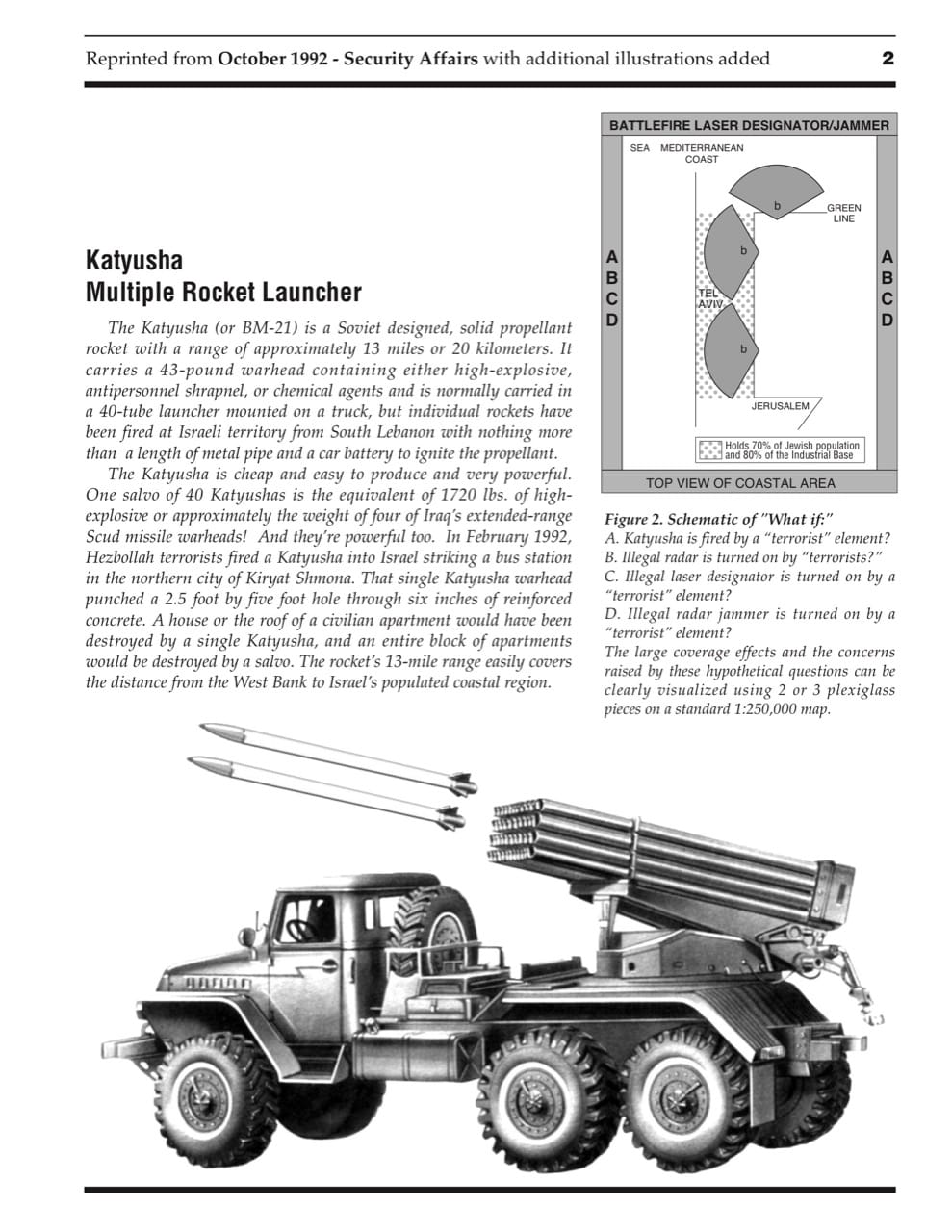

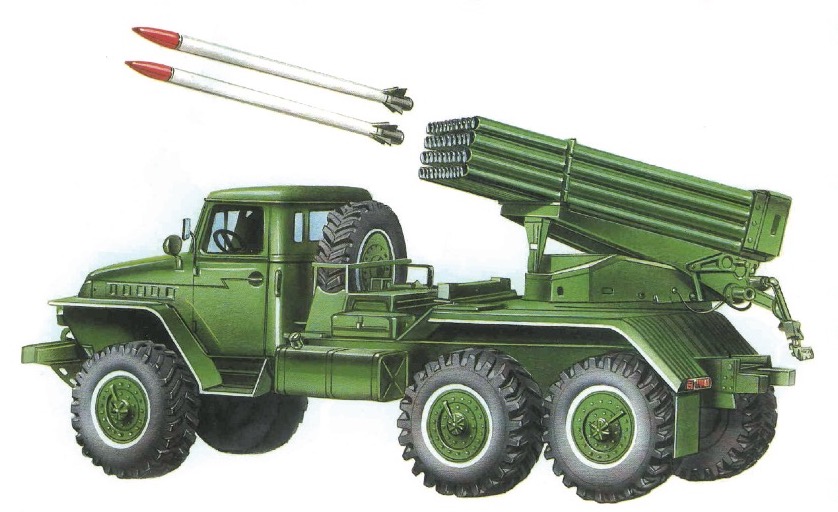

In addition, what right of action will Israel have if a Katyusha or other weapon is fired into Israel from the “demilitarized autonomous zone?” (see Figures 3 and 4) If such reprisal is restrained in expectation of justice being served by the authorities of the “autonomous zone,” what is the Israeli recourse when nothing happens? There will exist plausible deniability in the failure of the “autonomous zone” authorities to capture terrorist. Unlike in state-to-state relations, there is the likelihood that no one person or group of persons will have the authority or means to halt attacks on Israelis.

[/et_social_share_media]

[/et_social_share_media]

Figure 3.“Air space” and “air space control” by control of land and air.

- A. 3 pie pieces facing east in Judea & Samaria equal:

- a) Israeli Radar

- b) Israeli Jets

- c) Israeli Air Defense Weapons.

- B. All of which will blunt a strategic air or ground attack d*) from east.

- C. and D. Without a), b) and c), but with 3 pie pieces facing west and large pie slice pointed west like a knife, which represent:

- a*) Palestinian “Civilian” Radar.

- b*) Palestinian “Demilitarized” Helicopters.

- c*) Palestinian “light” Air Defense Weapons. “Light” = “Heavy” by Helicopter bay.

- d*) Palestinian Attack Aircraft - Knife - dagger.

Israeli Airbases of Ramat David and Lod

[/et_social_share_media]

[/et_social_share_media]

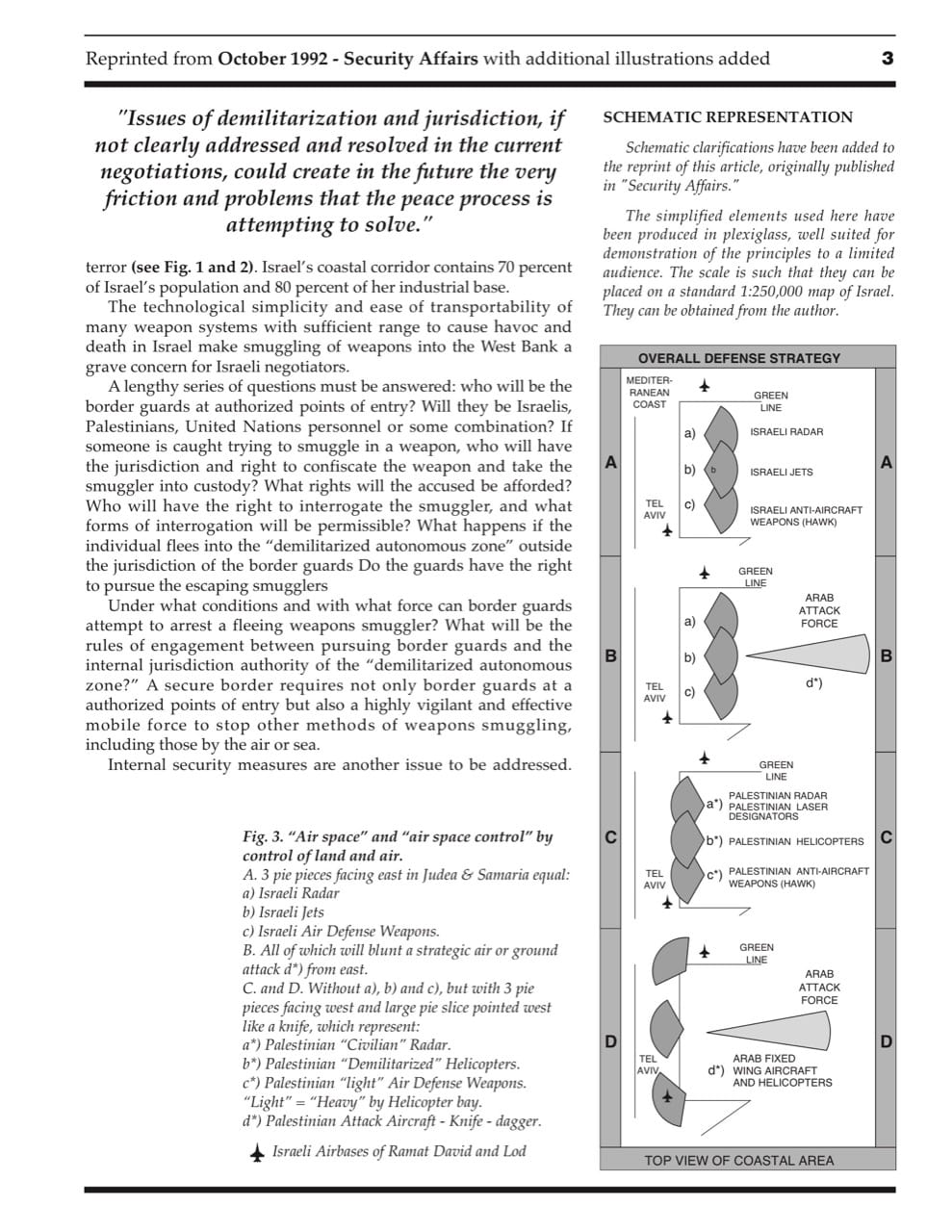

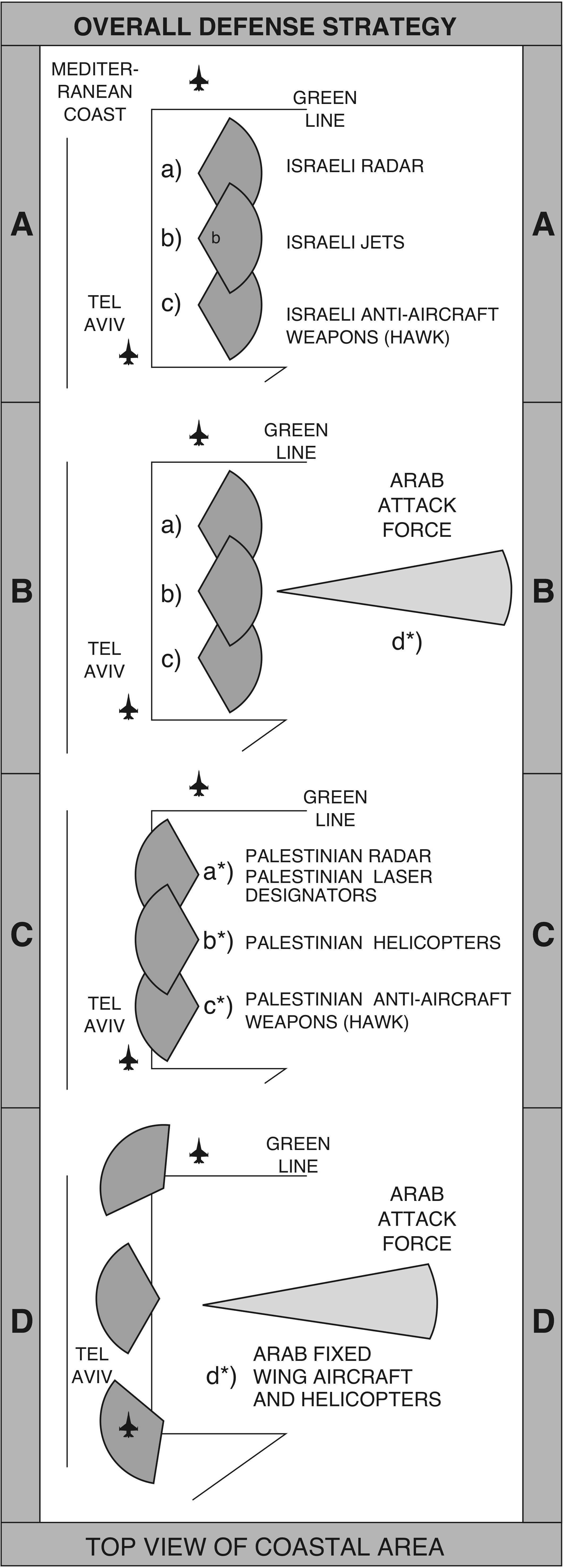

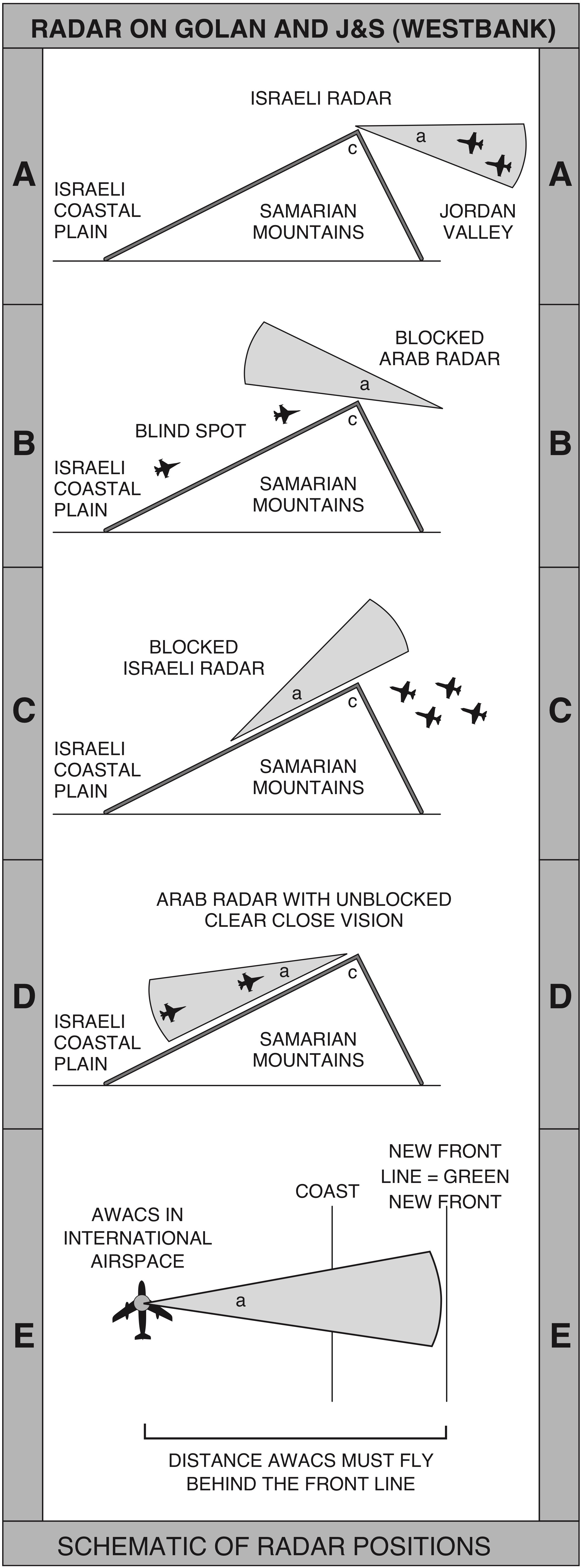

Figure 4. Radar - Line of Sight:

Applicable to the Golan and Judea & Samaria

- A. Israeli Radar on crest enables Israel to see out across Jordan Valley.

- B. Samarian Mountain Crest blocks out Arab Radar from Jordan from seeing critical Israeli Air Force bases.

- C. If Israel moves back to green-line, Israeli Radar will be blocked by Samarian Mountains.

- D. If Arabs control Samarian crest, they will have clear radar look into Israeli Air Bases and Mobilization points.

- E. Israeli AWACS (as a substitute for Samarian mountain based radar) operate far from front line (70 km) and therefore will be in international airspace and extremely vulnerable.

Issues of demilitarization and jurisdiction, if not clearly addressed and resolved in the current negotiations, could create in the future the very friction and problems that the peace process is attempting to solve. If a lasting and durable peace is to be created between Israel and her Arab neighbors, great thought, foresight and patience must be used to create a workable peace settlement.